What’s in a Word?

By Derrick Feldmann and Michelle Hillman

Overview

In many instances of gun violence, family members or friends noticed warning signs that people close to them were at significant risk of harming themselves or others. In fact, a 2018 FBI study of mass shooters found that the average shooter displayed four to five “observable and concerning” behaviors before their attacks—behaviors that are most likely to be noticed by friends, family members and others in their lives.

Consider these examples:

- Prior to the February 2018 school shooting in Parkland, Florida, the shooter was banned from carrying a backpack on school grounds for fear that he might be carrying guns - and had even been the subject of dozens of 911 calls to local law enforcement and the FBI.

- In the weeks leading up to the El Paso, Texas shooting in August 2019, the shooter’s mother had called the police about her concerns of her son and his assault rifle.

- Before the May 2022 Uvalde, Texas elementary school shooting, the gunman “gave off so many warning signs that he was obsessed with violence and notoriety in the months leading up to the attack that teens who knew him began calling him ‘school shooter.’”

With such indicators—known in many cases by law enforcement—why weren’t more actions taken to prevent these shootings? The problem in these and many other scenarios is that, in these states and at the time, local and state law enforcement had few effective means to prevent shooters from accessing guns even after such warning signs arose.

That is, until extreme risk protection orders (ERPOs). ERPOs, enacted to date in 21 states and Washington, D.C., many of which occurred as a result of the Parkland shooting (Florida included), have become a major opportunity to help mitigate gun violence before it starts. These statewide orders—also commonly known as “red flag laws”—provide a proactive way to stop gun-related tragedies by temporarily intervening to suspend a person’s access to firearms (and in some cases, ability to purchase firearms) if they are at a high and imminent risk of using one to hurt themselves or other people. Though the details differ by state, these laws typically empower family or household members and law enforcement officials to petition courts for a civil (non-criminal) order to temporarily suspend a person’s access to guns before they commit violence.

And they seem to be working. In the 21 states and Washington, D.C. where these laws exist, early signs show positive indicators, such as:

- In California, a study found that almost 30% (58 cases) of the ERPOs reviewed were used to disarm people who threatened mass shootings—including six cases involving minors, all of whom targeted schools.

- Indiana saw a 7.5% reduction in its firearm suicide rate in the 10 years following the enactment of its extreme risk law.

- In just the first three months after Maryland enacted ERPOs, at least four people who made threats of violence against schools were disarmed.

- A study by the University of Michigan Institute for Firearm Injury Prevention, in collaboration with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, reviewed more than 6,500 ERPO cases across six states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Maryland and Washington. Among the cases reviewed, researchers found that 10% of the petitions filed were in response to multiple victim or mass shooting threats, 20% against incidents at K-12 schools, 20% at businesses and 15% involving partners, their children and their families.

In June 2022, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act became law, the first major gun reform legislation in decades. Among provisions addressing mental health and school safety, the bill made a number of reforms to the current process for the purchase and access of a firearm. Within this area were incentives for states to develop and implement extreme risk protection order programs. Then in March 2023, the Biden Administration issued an executive order that among other things, directed federal agencies to similarly improve public awareness and increase appropriate use of ERPOs nationwide.

These actions and others generated a new, national focus on extreme risk protection orders. However, though such laws exist in 21 states and Washington, D.C., lack of public awareness of the laws and their use could be a barrier to wider implementation and success—and to their adoption in further states.

With this heightened focus on ERPOs, the Ad Council Research Institute (ACRI) and The Joyce Foundation recognized an opportunity to raise awareness and understanding related to these laws: Among gun owners and non-gun owners in the states and Washington, D.C. with existing ERPOs about how the laws work and how they can be used to keep communities safe from gun-related tragedies; as well as among the frontline first responders who will be most involved in petitioning and/or enforcing them at the local level.

Thus ACRI conducted a mixed-methods research study to understand current knowledge of and attitudes toward ERPOs, as well as identify the most effective way(s) to explain and build awareness of these laws with the general public.

Specifically, this research was designed to determine the public’s current level of awareness and understanding of ERPO laws, and understand the public’s attitudes towards ERPOs and the implementation of them, and if their perceptions change after learning more. Beyond these objectives, we sought to identify the best way(s) to educate and communicate about ERPOs to the general public.

Through the testing of messaging concepts (which we call “message frames”), this research intended to determine the key narratives and phrasing that most resonate with and motivate the general public to learn more about ERPO laws and how they’re used, which organizations can (and should) use in their efforts to drive broader awareness and understanding within the states and D.C. where these laws are enacted.

So how did we design this study? Let’s dive in.

Note to the reader: Due to the different law names across states and Washington, D.C., since ACRI undertook this study, the Ad Council has chosen to move forward with "Extreme Risk Laws" as the category name vs. ERPO. However, as ERPO was used for this study specifically, ERPO is used in this article as well.

Designing a study to identify knowledge, attitudes, and message response

The study consisted of multiple research methods and phases: a partner and expert convening (August 2022), initial qualitative and quantitative phases (October 2022 and January 2023, respectively), and final qualitative and quantitative phases (April and June 2023, respectively). Each phase was designed to dive deeper into participants’ knowledge and perceptions about ERPOs, and to test (and retest, and retest …) message frames that could be used to better position ERPOs to the general public.

Research Phases and Purpose

Pre-Research Phase (Partner/Expert Convening & Working Group)

With little to no existing communications research around ERPOs, it was critical to us at ACRI that the information we sought to uncover was backed by subject matter experts.

Prior to the launch of qualitative and quantitative phases, 25 key leaders in ERPO implementation and gun violence education (including representation from the mental health and disability space) gathered to lend diverse perspectives and issue-area expertise to guide development and message frames throughout the research project. We also selected six field experts to advise the research team throughout the project on items like discussion guides, questionnaires, message frames, and more.

Phase 1 Research (Qualitative/Quantitative)

- Understand knowledge, attitudes/perceptions and behaviors of ERPO

- Message test and optimizations

- Key behavior group analysis

Phase 2 Research (Qualitative/Quantitative)

- Updated message tests and optimization

- Key behavior group reaction/response to call to actions (CTAs)

- Trusted messengers for ERPO

When messaging goes wrong

The pre-study convening was critical in supplying the research team with expert-backed insights on ERPOs, which informed the beginning of our messaging journey. At the onset of Phase 1, we created a set of messages based on information and dialogues from our earlier convening of practitioners in the space. Thus in October 2022, we launched Phase 1 with a qualitative study via web interview with 40 general population people (from the states and Washington, D.C. where ERPOs are enacted), as well as with 16 law enforcement officials and 15 clinicians.

Failing frames, and the problem with “temporary”

Questions in this first phase were designed so the research team could understand how to help the American public understand ERPOs (what the law is, how it’s intended to help, and how to make it effective in leading the individual to gain more knowledge for future potential interest in working with a petitioner); learn how to inform and educate; have a clear view of an effective call to action; and identify polarizing language or words to use or avoid in future efforts.

In addition to questions, we showed interviewees six message frames to determine the messaging concepts (or combination of concepts) that respondents and law enforcement officials found most informative and helpful in explaining what ERPOs are, how they’re used and the benefits to individuals in crisis and the communities in which they live. These frames focused on key themes we learned from the expert convening:

- “The Big Pause” - Anyone anywhere can experience a moment when they’re at risk of harming themselves or others. In these heightened moments, removing access to guns gives everyone time to pause.

- “Time to Save Lives” - When a person is at risk of harming themselves and others and has direct access to a gun, it can take mere seconds for a risky situation to turn deadly. And when lives are on the line, especially involving loved ones, every second counts.

- “A Lethal Combination” - Plain and simple, a person who’s at risk of harming themselves and others and has direct access to a gun is a deadly combination.

- “An Act of Love/Caring” - The signs and symptoms of a person who’s at risk of harming themselves or others can be subtle. And for the person closest to you, you may be the only one who notices. When you notice, it’s time to act.

- “Moment of Truth” - When it comes to the subject of guns in America, it can feel hard to find common ground. But a strange thing happens when a person we care about is at risk of harming themselves or others, and we’re confronted with the stark, tangible reality of them carrying out an act of violence with a gun close at hand. Something happens when we separate the MOMENT from the DEBATE. We start to AGREE.

- “You Can Make a Difference” - When a person you know is at risk of harming themselves or others, you might feel incapable of help or support, or not even know where to begin. But when a person is at risk of harming themselves or others and you know that they have access to a firearm, your actions can mean the difference between life and death.

The Six Frames

In this phase, we heard overwhelmingly from general public respondents that they weren’t really aware of or familiar with ERPOs. After hearing a detailed description of the law, participants were generally in support of it—but several had questions and concerns about their effectiveness.

As for the frames? Well, for lack of a better word, they failed.

While respondents did say these frames worked to help raise awareness of ERPO laws, most of the people we interviewed felt they were incomplete and missing critical information about how they actually work, how laws are enacted, and more. Truthfully, respondents were critical of all frames: “The Big Pause” minimized the severity of urgent situations; “Time to Save Lives” wasn’t found to be direct enough; “A Lethal Combination” felt condescending. “An Act of Love/Caring” and “You Can Make a Difference” shifted too much responsibility to individuals (vs. to law enforcement, for example), while “Moment of Truth” felt too politically motivated.

Respondents were also really polarized around the word “temporary,” when used to describe how ERPOs are a temporary removal of firearms: On one hand, respondents—primarily gun owners—were afraid of “temporary” being a long time and infringing upon their Second Amendment rights; on the other, respondents—primarily non-gun owners—were afraid “temporary” wasn’t long enough.

While frame reactions were largely negative, the qualitative phase accomplished what we’d hoped: uncovering a deeper understanding of the American public’s current knowledge of ERPOs, identifying polarizing wording, obtaining direct feedback on message frames, and underscoring the need for a messaging approach that was better suited for the public, rather than focusing solely on what field experts are seeing. In other words, while experts provided an understanding from their perspective of what needed to be communicated (and their perceived challenges), such issues with the messages didn’t come out in the qualitative. In fact, new and different concerns arose.

Time to regroup

As a result of this phase, and before we could move into quantitative, we had some work to do. First, on audience: We found in the initial qualitative phase that clinicians were interested primarily in discussing de-escalation tactics and not communicating about ERPOs themselves. As such, the research team chose to omit this audience in future phases.

Next, on messaging: We had drafted six unique message frames based on expert insights and dialogues, and each of the frames failed in resonating with the American public. To optimize these frames, we needed to lean into the aspects people liked (explaining ERPOs, using succinct language), remove what they didn’t (any language that came across as condescending, politicized, jargon-y), and go deeper into details like how ERPOs are enacted.

We also had a problem with the word “temporary.” Because the word is a facet of the law itself (the temporary removal of access to a firearm), we couldn't simply omit it. Thus we had to determine an approach that would help the reader move past its polarizing effect.

As we prepared frames for respondent feedback in the quantitative phase, we made the decision to drop three frames from the qualitative entirely: “The Big Pause,” which we eliminated due to negative reactions in the qualitative that it wasn’t urgent enough; and two frames that respondents both felt put too much onus on individuals: “An Act of Love/Caring,” and “You Can Make a Difference.”

We applied strategic optimizations to the other three frames:

- “Buy Time to Save Lives” - The original frame, “Time to Save Lives,” was appreciated for its personal tone and clear explanation, but interviewees said it wasn’t direct enough. The revised frame used language that more directly connected how quickly a situation can turn bad with how an ERPO diffuses such a situation.

- “A Lethal Combination” - To optimize this frame, we removed language respondents felt was condescending (including phrases like “to be clear” and “plain and simple”) and further leaned into what respondents liked in the qualitative phase (the strong tone and assurance that ERPOs are intended to save lives and not punish people).

- “Moment of Truth” - This frame was designed to try to find common ground between gun owners and non-gun owners. In the optimized frame, we dropped language that respondents found political or jargony and instead incorporated a statistic that showed that most gun owners were in favor of restricted access in a violent situation.

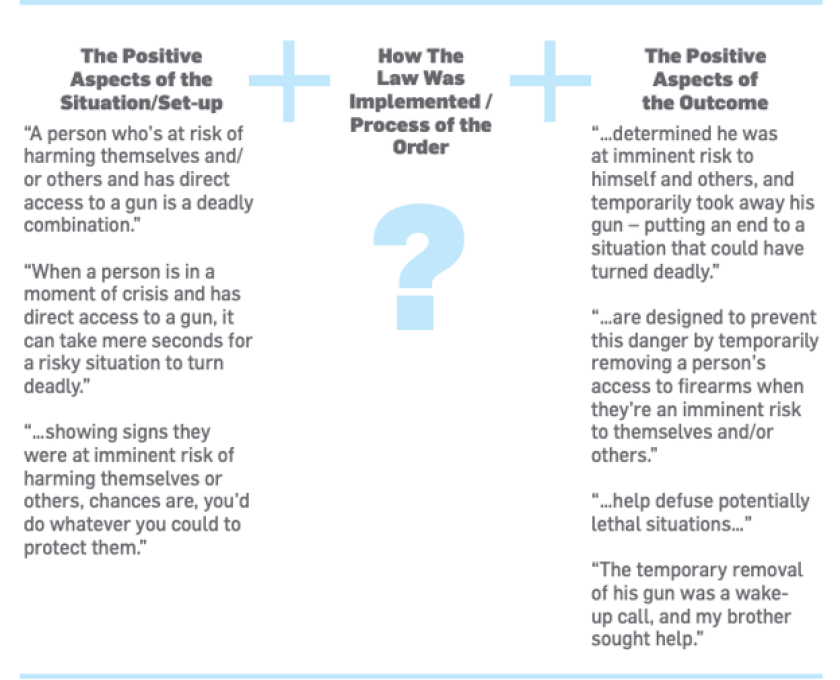

We also created an entirely new frame, “Success Story,” which told the story of an ERPO in action—which drew from qualitative feedback as well as best practices from our past messaging work around firearms. This frame was designed to illustrate a situation where an ERPO would be critical, and its success in preventing firearm-related violence.

With optimized and new frames in hand, on to quant we went.

Slightly better frame reactions, yet still lukewarm

After refining research questions and the message frames, in January 2023, we conducted a 20-minute online survey to U.S. adults ages 18+ to identify broader trends and approaches for campaign interventions and messaging. Respondents of the survey included both people from the general population and law enforcement officials, all within the states and Washington, D.C. where ERPO laws are currently in place.

General population respondents (n=5,065) were representative to the U.S. Census on age, gender, race/ethnicity and income within the 19 states and D.C. that have current ERPO laws. In addition to finding key differences among generational and racial/ethnic subgroups, noticeable differences were also seen among three key behavior groups:

- Gun owner/household gun owner

- Know someone in crisis

- Active duty/veteran

Note: In the survey, “knowing someone in crisis” was defined to respondents as having close family or friends who are currently experiencing or have experienced mental health struggles (emotional, psychological and social well-being) or who has reached a point of crisis (such as threatened harm to themselves or others).

All law enforcement respondents (n=200) held a position in law enforcement, carry a gun and have arresting capabilities. All law enforcement surveyed currently work in one of the states or D.C. with current ERPO laws.

Based on feedback from the qualitative phase, this initial quantitative phase presented a refined description of the ERPO law, which paid off some: After reading the description, most (about two-thirds) of quantitative respondents claimed to be aware of ERPOs, and in general, respondents found them to be positive and a means to keep people safe. But they still had questions and concerns about their effectiveness, and knowledge gaps in general about how they work.

And what of the optimized message frames, you ask? In this phase, respondents were shown each frame individually and asked to highlight the words or phrases they liked and disliked. They were then asked which frames they found the most informative and relevant, if/how motivated respondents were to learn more about the law based on the frame, and overall positive/negative reactions. In addition, law enforcement officials were asked which frames they believed would be the most informative, relevant and motivating for the general public.

To summarize, respondents felt fairly lukewarm about the frames.

Approximately half of respondents said they disliked nothing about each frame, but they weren’t overly excited about them, either. None of the frames stood out for being overly informative, motivating, or relevant among general population respondents, and many still were unsure about how the law is implemented or the overall ERPO process.

- “Buy Time to Save Lives” - Respondents liked how the frame connecting how an ERPO diffuses a situation that can quickly turn bad. Half of respondents said they dislike nothing about this frame, but “temporary” language was polarizing for some.

- “A Lethal Combination” - Respondents positively reacted to phrases about how ERPOs are designed to prevent negative action versus being a punishment. Again, half said they dislike nothing about the frame, though some were skeptical of the citation that 67% of gun owners support ERPOs.

- “Moment of Truth” - Like the other frames, half of respondents said they don’t dislike anything about this frame, but some were skeptical of the cited gun owner support in this frame as well. Themes of protecting loved ones and preventing harm/danger sparked interest in this frame.

- “Success Story” - Respondents were interested in/reacted positively to language that detailed a situation when an ERPO is needed (potential harm to self), along with how an ERPO specifically works (temporary removal). The phrase “call the police” was polarizing, while language at the end of the frame about the person getting their gun back was most disliked. Overall, like the other frames, half of respondents disliked nothing about the frame.

So what did we learn? For one, more information led to more questions—which can happen when too much detail in messaging is provided. Respondents craved more information on ERPOs from the initial qualitative questions and message frames, but this resulted in quantitative respondents having even more questions. From this, we learned that specificity and localization would be key: In many instances, this feedback indicated that future message frames should include more specificity on the ERPO process—not just why an ERPO may be needed or the overall outcome, but also how it was tactically implemented within the process, specific to the state it’s enacted within.

Bottom line: Even with detailed optimizations, reactions to these message frames were still somewhat tepid.

The problem with relevance

It was here that we realized not only a gap in respondents’ knowledge, but also a gap between those being surveyed and those likely to be impacted by ERPOs.

In most message frame testing at ACRI, we typically ask questions to determine if respondents find frames to be informative, relevant and motivating (to take further action on the topic). But with this research specifically, we identified a gap between the people in the sample and those who are most likely to use (or petition for) ERPOs in their lifetime, which likely skews overall findings.

To go deeper: A third (33%) of quantitative respondents in this phase said they know someone in crisis, which is the most likely group to be impacted by an ERPO. In contrast, the 67% of respondents who said they don’t know someone in crisis are much less likely to be impacted by an ERPO. This means that the sample is dominated by those without exposure to someone in crisis, and as such, attitudes may shift toward irrelevance due to the sample composition.

Even further, we identified in this phase just how difficult it is to craft one set of messaging to fully encompass the nuances of the law by state. Critical details of an ERPO differ by state—like who can petition for an ERPO to be enacted, the time it takes for an order to be carried out, the time a person’s firearm could be removed for, and more.

Despite low (perceived) relevancy, however, this research and the creation of preemptive message frames are still important for the public to understand and know how to leverage an ERPO should a situation arise—and for those details to be understood within the context of their own state’s order.

As we looked to move into Phase 2 (another round of both qualitative and quantitative), we knew further optimizations to the message frames were needed. In an effort to really streamline, we chose to move ahead with only two frames for this phase: An optimized version of the frame that performed the best in the second qualitative study (“Success Story”), and a new, extremely specific and detailed frame that would fill much-needed (and much-desired) knowledge gaps both of the overall ERPO process and with state-specific details (“Details by State”).

Unlike Phase 1, we also added a call-to-action to each frame, which when used in campaigns would invite audiences to learn more about ERPO laws in the individual’s state of residence.

And so onward we went.

When messaging goes (almost) right

The final qualitative phase (April 2023) was designed to dive deeper into the reactions, responses, and themes that were determined in the initial qualitative and quantitative phases. In this phase, we sought to further our inquiry into awareness and understanding of ERPO laws and how they work, test additional message frames, and further identify specific elements of the ERPO description and message frames to help the American public understand what the law is, how it is intended to help, and how to make it effective in leading behavior change.

This phase consisted of 32 online interviews with general population from a mix of the states and Washington, D.C. where extreme risk protection orders have been implemented.

So how did we do?

With “Success Story,” qualitative respondents liked that the frame communicated the speed of removing the gun in the situation, and that it featured a progression of risky behaviors that were observed. Respondents were glad to see that the person was able to avoid a longer ban, that they get better, and that the story implies the firearm was returned. However, they also felt the frame needed to go deeper into the ERPO process. They were unsure about some details, such as what the court warrants is “enough progress” to give back the gun. Additionally, several felt it was unrealistic that the dad in the story was readily willing to get help and did not get angry at the family member for intervening.

The new frame, “Details by State,” used a dynamic feature that populated specifics of the law to the respondent’s state of residence, so each respondent only saw details specific to their own state. Within this frame, information on the exact speed of the petition was well-liked by many, and the “emergency order” implies that this process can start immediately. Respondents also found it helpful to see exactly who can be counted among the petitioners, and less emphasis on the word “temporary” helped avoid confusion or pushback. Some respondents wondered where “evidence” comes from, and some people from states where the petitioner does not include family members were disappointed about the omission.

Overall, we found in this phase that participants still had some feedback and questions about the law itself and regarding the two message frames, but overall reactions weren’t as negative as in prior phases.

We were getting closer.

Final frame optimizations

As we looked to the final quantitative phase, we incorporated respondent feedback from the April 2023 qualitative phase to further optimize the two frames. For “Success Story,” we added more emotional language to bring in the reader and also went deeper into the court’s involvement to better inform the audience on how the person at risk was deemed to be a threat or not.

Most of the qualitative feedback on “Details by State” were personal disagreements with the law itself (which, obviously, could not be changed by the research team). However, we did further optimize this frame to more strongly communicate the support and peace of mind in contacting law enforcement for these risky situations, especially in states where law enforcement must file the petition instead of others (like family members). It also included deeper reassurances for gun owners about the careful handling and immediate return of firearms after due process.

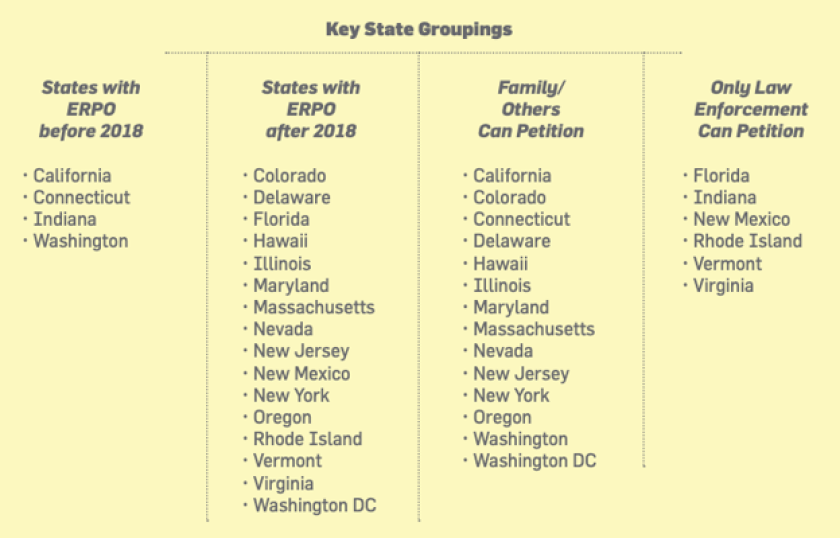

Finally, finally, we conducted the last round of quantitative research to further refine and understand the most effective way(s) to discuss ERPO laws with the general public. In this phase, we conducted an 18-minute online survey in June 2023 among U.S. adults ages 18+ to understand current perceptions of ERPO laws and if perceptions shift after learning more; and to identify the best way(s) to communicate ERPO laws to the general public, including the top trusted messengers, trusted sources and an optimal name for the law. This phase was especially designed to further test the optimized frames from previous rounds.

In this phase of research, we recruited participants from states not based on a proportion of population as previously conducted in prior rounds of research. The team at this phase ensured an almost equal sample from all states to report findings in aggregate.

Results were reported by:

- Total Aggregate: n=5,054

- States with an ERPO enacted before 2018: n=1,065

- States with an ERPO enacted in 2018 or after: n=3,989

- States where family or others (beyond law enforcement) can petition: n=3,360

- States where only law enforcement can petition: n=1,444

Note: For states with multiple temporary gun restraining order laws, we chose to test the laws in those states that included more than just a police petitioner.

So what were the results? On the positive side, both messages were perceived as informative and easy to understand. Situations when an ERPO is needed (potential harm to self), how it works and the positive outcome sparked interest overall with respondents in the “Success Story” frame. A quarter said they didn’t dislike anything about the frame, though mentions of violence and threatening behavior were polarizing for some.

In “Details by State,” describing what an ERPO prevents (tragedies/harm to self and others), the quick response and how it works sparked interest among respondents. Like with the other frame, a quarter said they didn’t dislike anything about the frame, though some did not like details describing specific parts of the order itself (such as who can petition, or the length of time needed throughout the process).

Neither frame, however, were deemed particularly motivating for respondents to find out more information about ERPO laws, nor were they found particularly relevant among respondents (and only slightly more for those who know someone in crisis). For both frames, respondents indicated they were only moderately likely to take further action—like find out more information (how to identify someone in crisis, how to help someone in crisis by using this law, how to start a conversation with someone in crisis, about the law in general), or talking (to a friend/loved one/trusted person about their mental health, to a trusted person about the law in the message, etc.).

When forced to choose which message would motivate them more about ERPO laws, “Success Story” slightly edged out the “Details by State” frame.

Our learnings: From dismal to good, and beyond

For agencies and organizations in the 21 states and Washington, D.C. with existing ERPO laws, what are next steps? How do you craft an ideal messaging campaign to raise the public’s awareness and education of what an ERPO is and how it works, given that most of your audience is likely never going to be impacted by one?

First, it’s critical to understand and accept just that: Most of the general public is not your target audience here. Communicators and organizations should first focus on targeting three key behavior groups for information and education on ERPOs:

- Those who know someone in crisis

- Gun owners

- Active duty military/veterans

Those who know someone in crisis (e.g., struggling with their mental health or have reached a point of crisis) are the people who are most likely to be impacted by an ERPO, making them a key audience focus for information and educational efforts. Gun owners could also potentially be impacted by this law, if they (or a gun owner they know) were ever in a moment of crisis and at risk of harm to themselves or others.

Gun owners and active duty military/veterans indicated in the study they were more aware of and familiar with ERPO laws than the general public. However, these two groups also indicated they were more worried than the general public about potential negative impacts the law could have on individuals, such as the law being inappropriately used (e.g., to get someone in trouble or for revenge), a negative impact to a person’s future housing option or employment opportunities, or damage to a person’s criminal record. However, as a civil (and not criminal) procedure, the evidence that these negative beliefs are purely points of misperception to address, which illustrates an opportunity to further educate these groups on ERPOs and their implications.

As a secondary measure, campaign efforts can target the general public in the states and Washington, D.C. where ERPO laws are currently enacted, though with the understanding as noted above, that many/most will not be impacted directly by an ERPO in their lifetime.

Within these audiences, our team identified the following key recommendations for messaging and campaign efforts:

- Provide detailed information on ERPOs. The public wants information on ERPOs in a clear and concise manner that answers their questions and fills in knowledge gaps. In particular, they want to understand the law and how it works: the type of evidence needed to file a petition, how to start the process, when to use the law, how it will help individuals in crisis, the impact on the individual being filed against, and more. In addition to information on the law, respondents also indicated they wanted more information or resources on how to identify and/or help a person in crisis.

- Incorporate real scenarios and how ERPOs prevent them. In addition to information on how ERPOs work in their state, the public wants to know why ERPOs are needed. Across all research phases, messaging that detailed specific situations (such as suicides or mass shootings) and how ERPOs prevent them through temporary firearm removal strongly resonated with respondents.

- Localize ERPO details by area/state. Providing audiences with localized, state-specific information is also key. Details of the laws vary from state to state, so it’s confusing for audiences to be given generalized (or simply incorrect) information. From state-specific names of the law (e.g., Extreme Risk Protection Order in many states; Illinois’ Firearms Restraining Order; Indiana’s Jake Laird Law) to policy details (who can petition, time frames), it’s critical for organizations and communicators to include state-specific details and/or resources whenever possible.

- Recognize challenges with the word “temporary.” ERPOs are temporary laws, a factor that was often a sticking point for audiences across all research phases. Messaging that describes how ERPOs are temporary led some non-gun owners to question the timeline and validity of the process to get the firearm back. Conversely, gun owners needed reassurance that it would only be temporary and were skeptical of the information needed to enact the law, or were concerned about potential Second Amendment violations. To clarify, however, respondents didn’t react negatively to the use of the word, but instead to the meaning of temporary within the law itself—meaning organizations and communicators shouldn't shy away from the use of the word temporary in campaign efforts.

- Don’t overlook crisis information in the ERPO discussion. Besides information on ERPOs, respondents in the study said they want more information and resources on mental health crisis: how to identify if someone is in crisis, who to contact if such a situation arises, how to start a conversation with someone in crisis, and general resources for mental health. Those who know someone in crisis already are even more interested than general population respondents in such resources.

When “pretty close” equals success

For our ERPO Study, it was both the journey and the destination that proved to be important—pushing through failures with continued work and optimizations to truly understand what works with the general population in the states and Washington, D.C. with ERPO laws. The ACRI team undertook this study for the better part of a year, and even through multiple phases and expert input, we didn’t find the perfect answer. For some, however—given that the law itself can be polarizing (as well as messaging describing it), and that this law won’t be relevant to most—“pretty close” may well count as success when it comes to ERPO communication and messaging. And for now, that’s all we can ask for.

Download the ERPO Research Study and toolkit here.